What happens when a couture gown is left to rot in the ground? In 1993, Turkish Cypriot designer Hussein Chalayan found out, burying silk dresses with iron filings in a friend’s London garden for three months. The dresses emerged rusted, corroded, and shimmering with oxidised patterns, proving that mud and decay could be just as dazzling as sequins. Chalayan’s alchemic experiment is at the start of Dirty Looks: Desire and Decay in Fashion at the Barbican Centre, an exhibition showcasing 60 designers’ embrace of ruin, and whose garments – whether buried, weathered, stained, or consumed by microbes – probe deeper questions of beauty, mortality, and the ethical and political future of the fashion industry. Dirt and decay, it seems, are where some of fashion’s most radical ideas take root.

“We wanted to address sustainability without making an environmentally-focused exhibition – most people already know the [environmental] issues,” curator Karen Van Godtsenhoven explains. “Instead, we focused on how designers grapple with cycles of life and regeneration. Not every designer in the exhibition is strictly sustainable, but many explore these themes poetically: life, decay, rebirth and returning to earth. For younger designers, the urgency is sharper: they graduate into an oversaturated industry and wonder: ‘What’s left to make? What is possible now?’”

Hussein Chalayan, Temporary Interference, spring/summer 1995. Courtesy of Niall McInerney/Bloomsbury/Launchmetrics/Spotlight.

Maison Margiela Artisanal spring/summer2024. Courtesy of Maison Margiela

From Chalayan, the exhibition moves to Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s autumn/winter 1983 post-punk Nostalgia of Mud, a collection that flirted with rebellion, retaining punk theatricality in a softer, romantic style. Thick shearling and suede coats in dirty-beige tones were layered over tiered skirts, chunky woollen socks, and oversized hats. “It was still rejecting bourgeois society,” van Godtsenhoven explains, “but in a more playful, romantic way than punk.” And the oversized Buffalo Hat? Pharrell Williams may have turned it into a meme at the 2014 Grammys, but for Westwood, it was a nod to Aymara and Quechua women in Bolivia who turned the colonial bowler into a symbol of cultural pride. In Thatcher’s Britain, the collection landed as both pastoral fantasy and anti-consumerist rebellion that was playful, radical, and worlds apart from the polished glamour of the 1980s.

Across the Barbican’s lower galleries, the walls are draped in uncut toile (with the fabric to be donated to London’s fashion schools after the show closes), and decay becomes quite literal. Copenhagen’s Solitude Studios allow their textiles to rot in ancient bogs, microbes munching away to stain, erode, and reshape them before they’re reassembled. London-based Alice Potts even = goes as far as to crystallise human sweat onto her dresses, and in the exhibition, her mid-20th-century Madame Grès bodice glimmers with pearls of perspiration. Priya Ahluwalia’s spring/summer 2023 collection Symphony transforms deadstock fabrics sourced from the UK, India, Portugal, and Italy into layered patchworks that reflect her Nigerian and Indian heritage, London upbringing, and the music that informed her style – from Lauryn Hill and Missy Elliott to Fela Kuti and Bollywood hits.

Paolo Carzana, autumn/winter 2025, Dragons Unwinged at the Butchers Block, Photograph by Joseph Rigby. Courtesy of Paolo Carzana.

Alexander McQueen autumn/winter 1995. Vogue Archive

Elsewhere in the exhibition, dirt becomes a medium – literally. An Issey Miyake tsutsugaki dress swirls with ghostly white patterns, created by a mud-resist dyeing technique, set against deep, indigo fabric. In Miguel Adrover’s Birds of Freedom/MeetEast autumn/winter 2001 collection, Egyptian cotton gowns bear streaks created by sand and water from the River Nile, the surface textured by sun-bleached patina, patterned with birds mid-flight. In Alexander McQueen’s Highland Rape (autumn/winter 1995), delicate lace is shredded and caked in mud, a scandalously poetic ode to the messy, gendered politics of decay. Dirt has never looked so intricately delicate, or unsettlingly visceral.

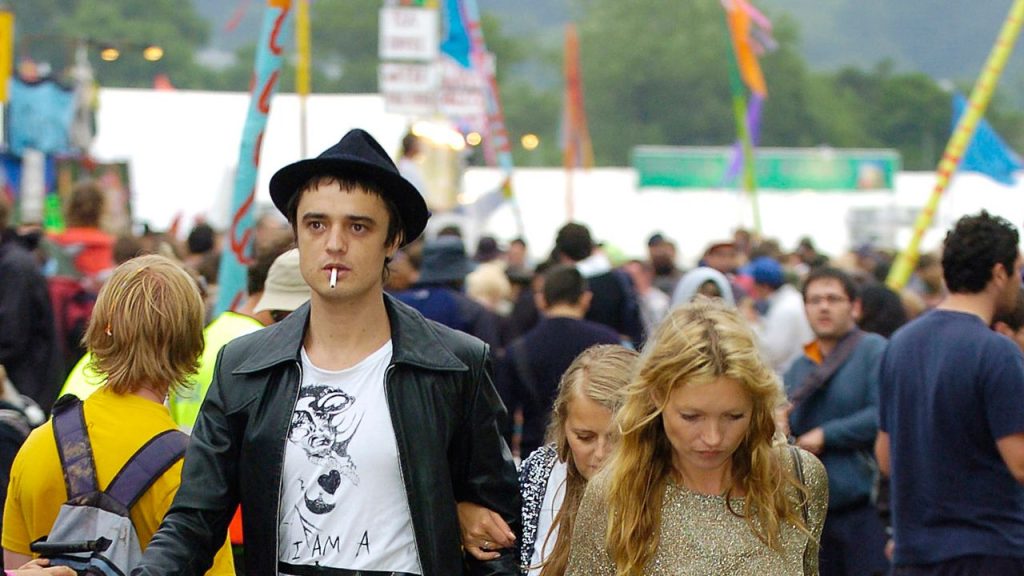

Another room is dedicated to Tokyo-based Yuima Nakazato’s collections and film Dust to Dust (2024), documenting how he transformed towering textile waste from Nairobi’s Gikomba Market into pieces that later graced the Paris couture runway. Welsh-Italian designer Paolo Carzana treats fabric as if it were alive, bruising, creasing, and dyeing it with plant and mineral pigments across his Trilogy of Hope (2024–25) collections, producing richly textured, scorched-hued surfaces imbued with organic texture. At the exhibition exit, Kate Moss’s Glastonbury-worn Hunter boots sit beside Queen Elizabeth II’s glossy black Wellingtons, a reminder of our shared urge to get muddy and connect with the earth.